Head on over to my main author website for information about All the Ghosts in the Machine, to include links to press, events, podcasts, reviews, and other publications.

Head on over to my main author website for information about All the Ghosts in the Machine, to include links to press, events, podcasts, reviews, and other publications.

Author Archives: dreprkasket

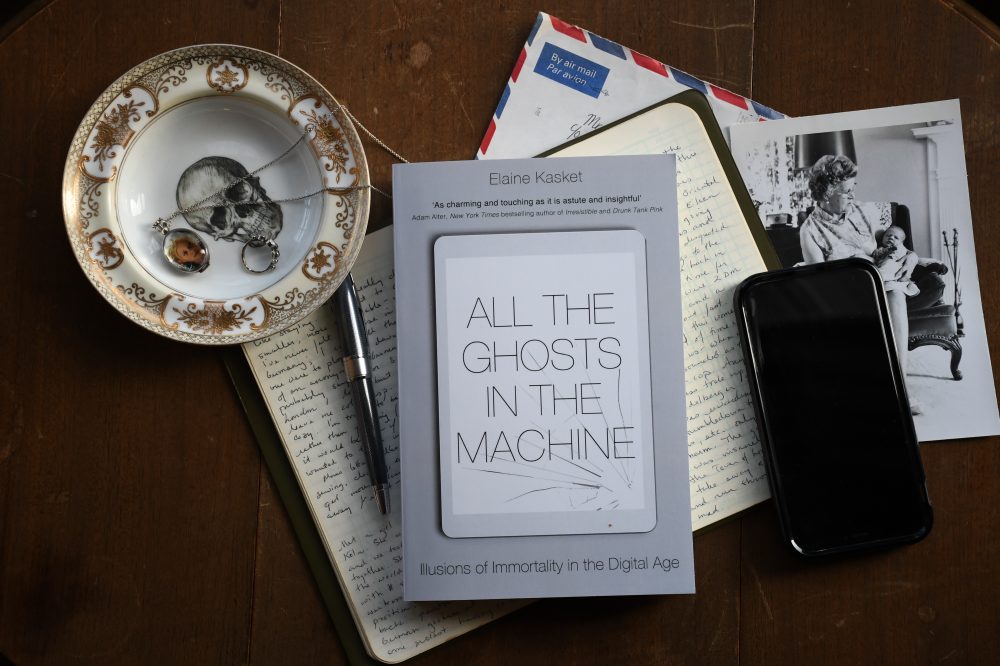

All the Ghosts in the Machine, 25.04.19

Photo credit (c) Elaine Kasket 2019

Photo credit (c) Elaine Kasket 2019

At long last, All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age will be available worldwide on the 25th of April. As with any book – fiction and nonfiction alike – the creative process is full of twists and turns, and an author often don’t end up where she thinks she will. I hope – no, I know – that in reading this book and delving beneath the superficial ‘death on Facebook’ type of headline, you will share much of the surprise and wonderment I experienced when researching and writing the book. I hope that the last chapter, in particular, will give you a clear sense of direction for what you want to do in your own life.

There were too many key realisations for me to count in the making of this book, but here’s a smattering, just as a teaser.

- There are currently about 4 billion people connected online worldwide. In 2099, there may be about 5 billion dead people still connected on Facebook. If you’re not sure why this is so significant, prepare to be much better informed!

- If you’re only thinking of your ‘digital footprint’ as your interactions on social media – if you ‘do’ social media – there’s a whole lot that you’re not thinking about. And the things you’re not paying attention to are the things that could say the most about you after you’re gone. Maybe that won’t prove a problem for the ones you leave behind. But then again…

- There is perhaps no better illustration of the extent to which Big Tech (Google Apple Facebook Amazon) ‘owns’ us, and the extent to which we have lost control over our personal information, than observing what happens to our data when we die.

- The inventor of the World Wide Web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, argues that we have lost our way. The Web we have, he says, is not the Web he intended, which is why he’s pushing for a new kind of web where control is wrested back from big tech and re-delivered into the hands of individuals. I get where he’s coming from. If ever there were a powerful argument for web decentralisation, it’s watching what happens to our ‘posthumously persistent’ online data, controlled and managed by profit-driven companies.

- Any sort of law or regulation from the pre-digital age struggles to cope with digital ‘stuff’. That includes laws of succession, which govern what we can and can’t leave to others in our will. Bad decisions are already being made by legal minds that don’t fully grasp understand the differences between the material and digital context. For example, if you currently think accessing a dead relative’s Facebook Messenger is the same thing as inheriting a box of physical letters – as a high court in Germany recently ruled – his book may convince you otherwise.

- Although algorithms reinforce the outdated notions that grief progresses in phases (just try Googling ‘stages of’ and see what pops up first), this isn’t the case. Grief is idiosyncratic, and all mourners need and want different things. Does the Internet change how we grieve? It sure does. But what’s more, it often legislates how we can grieve. And that’s a problem.

If this collection of teasers piques your interest, well, you’re in a growing club of people who are realising that online isn’t forever and that ‘digital legacy’ is a whole lot more complicated than we might have imagined.

Want to learn more? Here’s how:

Anywhere in the world: You can get the audio version of All the Ghosts in the Machine on Audible or Storytel. I was really happy to be asked to read the book myself, which is a gift for any author. You can also get the e-book in English on Amazon and Kobo if these are available in your country.

Everywhere except North America: You can purchase the English-edition trade paperback of All the Ghosts in the Machine online or through your local bookshop.

North America: You can get the trade paperback in early 2020, a fully up-to-date edition with the most recent developments incorporated. Until then, enjoy the audiobook and and e-book edition!

Other languages: The book is currently being translated into Chinese, Korean and Romanian, with further foreign-language editions to come. Stay tuned.

Please visit my author website and follow me on Twitter and Facebook for further updates!

An Academic’s ‘Great Escape’ into Writing for Trade

As she pulled her chair forward to conspiring distance and sat down next to me, her eyes were wary and her overall demeanour skittish. She opened her mouth, then shut it again. Her cheeks were flushed, her chin was ducked low, her shoulders were hunched. The woman was the very embodiment of shame. What on earth could her errand be? Was she about to ask me where she could find some illegal drugs? Was she hoping to procure a hit man? Was she about to confess some unpardonable sin?

‘I’m thinking of leaving academia,’ said my fellow conference attendee. ‘Maybe you can help me. How did you get out?‘

Oh dear, another one. I’d thought as much – all the indicators were there. Since leaving my position as a Principal Lecturer and Head of Programmes at a UK university, I’d been approached this way at least a dozen times. I was curious about the apparent extent of her terror, for she was simply asking me a career question, not risking her life to plot with me about digging a tunnel out of Stalag Luft III. ‘Why are you whispering?’ I asked.

We were miles away from her employer, but nevertheless she cast a glance to either side of us and quickly checked over her shoulder. ‘I’m not sure,’ she said. Even so, her voice remained hushed throughout the rest of the conversation.

I do have a hypothesis about this, one that I’ll explore in a future blog post. Leaving one’s job in higher education might not be easy for a variety of reasons, but I reckon that life in modern UK higher education institutions (HEIs) is giving faculty a kind of individual and collective inferiority complex. However extraordinary their gifts, however solid and potentially transferable their skill sets, academics don’t think there’s anything else they can do, anywhere else they can go…at least, not if they want to survive. Huge workloads and the tyranny of the Research Excellence Framework (REF) and Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework (TEF) force everyone from lecturers to professors into insularity, unable to think beyond the immediate demands of their jobs. The fences surrounding the ivory tower appear to have grown higher and more impenetrable – no wonder the chances of carrying off an escape attempt are perceived as slight. But I didn’t feel that I had a choice. There was something I wanted and even needed to do, something my employer treated with disinterest and perhaps even mild disdain, something that was judged to have nothing whatsoever to do with my job. I hesitate to say it out loud, even today.

I wanted to write a book…for trade.

That’s right. Trade. Not for an academic publisher. Not for an academic audience. A general, non-fiction, popular science type of book, aimed at a broad readership, something that wouldn’t even cause a blip on the REF radar. Now that All the Ghosts in the Machine is submitted, accepted, and awaiting publication with Little, Brown UK, I’m reviewing the last year of my life and contemplating the next one, and I can honestly say that making the leap was one of the best decisions of my life.

If you’re an academic who’s also interested in being a public intellectual, let me hasten to say that writing a book for a trade publisher, aimed at a general audience, is not the only way to pursue that. But it’s what I’m going to talk about here. Maybe you think your primary barrier to writing for trade is time, perhaps related to your institution’s reluctance to privilege this kind of activity over, say, the production of research articles for 4* journals. Maybe it’s confidence, and if that lack of confidence stems at least partly from ignorance of this sector, I would like to help you out a bit by offering some nuggets of wisdom drawn from my learnings of the past year.

Read on for my top seven tips for academics who dream of writing for trade.

Death + Digital + Creativity + Humanity

Maybe you’ve had this kind of experience. You’re about to stand up or perform in front of a group of people, having been touted as an expert in something, or an actor that knows their lines, or someone who can carry off a violin solo, or who can dance without falling over. Suddenly you think, ‘There’s been some terrible mistake. I’m going to let these people down. I’m going to let myself down. In fact, I just might die of humiliation right there on stage.’ Did someone just whisper ‘you’re a fraud’ in your ear, or were you imagining it?…sorry, am I making you break out in hives?

I’m not saying I got to that point, mind you. I’m one of the lucky ones who’s never been afflicted with crippling stage fright. Nevertheless, as I took my seat at Hill + Knowlton’s Creativity + Humanity, doing my best to be unobtrusive because the event had begun, I felt a frisson of unease. The people on the stage were talking about brands. Then someone with an impressive title assumed the podium to talk about the future of banking and to give me a PowerPoint inferiority complex. Then an international panel filed on stage to speak about energy. Rummaging in my branded canvas bag and encountering a paper packet of Lego along the way, I located a card that described the sector knowledge and specialist expertise that One H+K offered and scanned it for any terms at all that resonated with me as a psychologist. I found ‘Behavioural Science Unit’ and ‘Issues + Crisis’, which had the ring of familiarity, but there were a lot of other words too. ‘Financial + Professional Services.’ ‘Consumer Packaged Goods.’ ‘Energy + Industrials.’ I know people in these fields, but I can’t picture what they do at work. Would anyone in the room have any interest whatsoever in what I had to say?

I’ve learned that when you’re worried about something like this, often it’s best to just name it, which I did. (When I eventually see the video, I’m sure it won’t sound this slick, but it went something like this.) ‘I’m Elaine Kasket,’ I said. ‘I’m a psychologist. And you are not my usual audience. In fact, I don’t know what many people in this room do.’ Having confessed this, and having noticed that nothing bad happened as a consequence, I began to breathe more freely. ‘But I’m guessing that many of you in this room, directly or indirectly, and without necessarily realising it, are in a position to have an influence on people’s experience with regard to the digital remains of the deceased.’

The more I spoke, and the more conversations I had with people at lunch afterwards, the more I realised just why I shouldn’t have been worried. This is relevant – incredibly relevant – to all sorts of people. Every organisation and every brand represented in that room has control of some sort of digitally stored data about people – data that could be sentimentally or financially significant to someone – whether it’s associated with employees, clients, users, account holders, customers, service users, or patients. I was reminded of what I’ve known all along, which is that this is a critical time to be considering this issue, and it’s important to so many people who haven’t even thought about it yet. The Q&A that I did with Megan after the event is part of my argument as to why that’s the case, and it was also an opportunity to think further about what creativity means to me, which was already on the docket for a blog post in the near future. Follow the link, or read it reproduced in full below. Thanks again to H+K Strategies for a great day!

Disturbing Remains

When I arrived at St. Leonard’s on Shoreditch High Street, the film crew looked distinctly gloomy. Their solemnity wasn’t due to their being about to descend into the dusty crypts under this 1740 building, at least not yet; at that point, it was because some organisation or another was holding a big party in the churchyard. The sound system was just kicking into gear, pumping out music on a sunny Sunday and threatening to interfere with the audio for the mini-documentary we were there to film. A party atmosphere wasn’t what the director had been anticipating or intending, and furthermore, we were having trouble gaining access to the underworld beneath the church. The caretaker hadn’t yet arrived to unlock the door, which, when we arrived, was blocked with rubbish and festooned with a string of bright yellow happy-face balloons. When he eventually appeared, though, we realised that there was no cause for concern, as far as filming was concerned. Down in the depths, behind and beneath thick walls and floors, you could barely tell whether it was day or night outside, much less hear evidence of revelry and dancing. We wended our way through dim corridors, using our phones as torches and looking for places to film.

On one hand, this was an incongruous place to be shooting a film on ‘E-Life After Death’. Modern people’s online ‘afterlives’ or digital traces are made up of odourless bits of code and complex arrangements of colourful pixels, but our environment in the crypt was an entirely different sensory experience. While the atmosphere outside was sunny and warm, down there it was cool, grey, and slightly damp. Every surface we touched, accidentally or on purpose, left thick smears of dust on our skin and clothes. No one said it out loud, but I was conscious that – along with the musty smell – I was likely inhaling minute particles of humans that had been dead for hundreds of years. Doors to vaults were virtually all open or absent, with the bricks that had once walled them off scattered about the uneven floor, tripping us up as we arranged cameras, lights, and filming positions. Through the gaping entrances we saw coffins stacked atop one another, some broken or turned on their ends. ‘Oh god, that’s a jaw bone, isn’t it?’ said one crew member, pointing the light from his phone into a collapsing casket. ‘Shit,’ said another, treading on something. ‘I’ve stepped on a bone. Oh, it’s a stick. No, shit, it’s a bone, look, it’s a human bone.’ Working out whether he’d directly disturbed already-scattered human remains seemed to really matter to him, almost as though he needed to determine whether he’d done something ‘wrong,’ whether he should feel unnerved or even guilty.

I was more nonplussed than they, having visited quite a few crypts in my time. This is partly thanks to the periodic ‘open days’ held in the Magnificent Seven cemeteries in London, which usually involve opening the crypts too. Still, I could understand their unease. Disturbing physical human remains isn’t usually something we undertake deliberately or view lightly. But interestingly – and at the heart of the documentary we were making – is the fact that we encounter the digital remains of the dead online all the time. They are everywhere we go, whether they announce themselves or not. They’re on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Trip Advisor, Amazon, LinkedIn. They’re on the comment threads under news stories, on the blogs, on websites of every stripe. And if you think about it, we often disturb those remains.

Strangers like us had clearly been down in these crypts many times before, and the resting place of nearly every 18th- and 19th-century person buried there had been disturbed, disrespected, and cluttered up with rubbish. Maybe you would never do that, but online you might find yourself picking over the digital remains of a dead person like a jackal. It’s not just strangers that do it. Sure, trolls can come along with their cruel insults and senseless smears, but well-meaning parties disturb digital remains too. Family may deny access to or even destroy digital legacies, so that other mourners who arrive at the online graveside find a barred door, or an empty vault. Corporations, too, have their rules about what can and cannot be done with digital remains, with the result that the memories of the deceased that are preserved don’t always constitute the peaceful, respectful picture that some might wish. When a company that stores or manages a deceased person’s data goes out of business, they may cart digital remains away with them, robbing the grave as they file for bankruptcy. So think about it. We’re perpetually accessing, embroidering upon, editing, destroying or otherwise messing with digital remains online, and yet it doesn’t give us anywhere near the same pause that knocking in a crypt door would (hopefully) provoke. Maybe it seems obvious why that is. But maybe it’s also worth reflecting on why we see it so differently.

Look out for the eventual documentary on BBC Ideas, airing date to be determined.

Dear Zoe, This is Where You Came From

My 8-year-old very English daughter went to a very American summer camp last week, in the middle of a forest, near a great U-shaped bend in the great Ohio River. In a quiet house, with a lot of time on our hands, my mother and I sifted through some of the boxes full of photographs, letters, and other ephemera that she and her cousins had painstakingly assembled over the years, the repository of family history of which she is now a guardian. Synthesising it with the information available about our family on the Internet, it was a lot of information and terribly confusing. People had lots of children, they didn’t seem to vary the names they used very much, and I kept getting everything mixed up. The only way to keep it straight in my head was to make it into a kind of story. Why not? I thought. In addition to being an efficient way of organising information in my head, it could be a nice thing to pass on to the next generation. Realising that there was a one-way email system available to contact campers, I decided to write a letter to my absent daughter.

***

Dear Zoe,

I have been doing some research about your ancestors, following the line of mothers down through the generations. Zoe, Elaine, Beth, Elizabeth (your middle name is all because of her), Beatrice, Annie, Mary, Katherine. Katherine is your great-great-great-great-great grandmother, and you share something with her, even though she lived long ago. Mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, lives in our cells and helps make us what we are. mtDNA is special – it makes up only a little part of our genes and is only passed down from mother to daughter. If you had genetic testing, it could tell you who your mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother was all the way back in history. We don’t need genetic testing, though, for me to tell you a true story about Katherine, with whom you share 37 genes.

As far as we can tell – people didn’t always know exactly how old they were back then – Katherine was born in 1822 in County Longford, Ireland. Believe it or not, if that year is right, she was only 12 years old – only four years older than you are now – when she married your great-great-great-great-great grandfather, James, in 1834. James was from County Longford too, and both he and Katharine were Irish Catholic. He was an adult and she was a child – that wouldn’t happen anymore! Not long after the wedding, James and Katherine decided that it would be a good idea to go and live in America. They didn’t have aeroplanes then, so it was a long and often dangerous boat journey across the Atlantic Ocean. James decided that he would go first and check it out. Sailing across sea, he landed in New Orleans, down south in Louisiana. Perhaps he didn’t care for such a hot and swampy place after the cooler weather of Ireland, so he got a job as a ship’s mate and travelled north, up the big wide Mississippi River. The Mississippi feeds into a smaller river, the Ohio, which is the river that you can see from Grandmama and Pop’s house. (You’ve been on that river on a boat, which gives you something else in common with your great-great-great-great-great grandparents!) He looked around Louisville and liked what he saw, so he sent his young wife Katharine a letter encouraging her to come and join him.

Letters between America and Ireland travelled by boat and would have been very slow, and Katherine must have been waiting to hear from him for months. When she finally received his message, she quickly made arrangements and got on a ship. She can’t have been very old then, only a very young teenager, and she must have been frightened. She must have been quite brave, but apparently she later said that she would never again trust her life to a ‘handful of sticks’, so it must not have been a very sturdy-feeling vessel. After a long while she arrived in a big, dirty, unfamiliar city in an strange country. New York was pretty crazy back then and looked nothing like the city that it is now. James collected her, and she must have been very happy to see a familiar face.

Very soon after Katherine arrived, she and James had their first baby, Mary. First James got a job in Butchertown in Louisville, working as the big boss of a large pork house – that’s where they make pigs into sausages. They moved across the river to New Albany, Indiana, in 1848. They had more children, and James got a job preparing the ground for railroads, including one that ran from New Albany to Salem. Katherine stayed at home with Mary, John and Ellen. (We don’t know which house they lived in, but there are still many houses in New Albany that were around a long time ago, so maybe we could find it someday.) In 1850, Katharine gave birth to the couple’s fourth child, Edward. She’d been having babies since she was very young, and maybe this last childbirth made her a bit weak, for when little Edward was only seven months old, Katharine died. She was only 29 years old. That’s quite sad, isn’t it? Mary was a young teenager and could help look after the littler ones, but it was a lot for their father James to cope with, so he looked for a new wife. He married a second time – she was called Mary too – and she was quite a bit younger than him, just like his first wife. The family moved to Cloverport, Kentucky. That’s on the Ohio River too, and back in those days you would have most likely travelled there from Louisville by boat. Now it’s about 1-1/2 hours away by car. James and his new wife started a grocery store in Cloverport, and his oldest daughter Mary started to look around for a husband – that’s what teenage girls did in those days.

Pretty soon, your great-great-great-great grandmother Mary (that’s four greats!) met someone who was an Irishman like her dad, although this man was from County Donegal, not County Longford, so he would have had a very different accent. He was a few years older than her, but Mary thought he was pretty nice. His name was John Haffey, called Haughey back in Ireland. They got married in Cloverport when she was just 18 years old – that sort of thing was pretty normal back then too.

She moved in with her new husband, which was probably a good thing because her stepmother – who was only a couple of years older than Mary! – was busy having loads more babies and it would have been pretty annoying. John turned out to be a pretty successful guy, so John and Mary must have had a nice life down in Cloverport, Kentucky. Ten years after they married, when the city needed someone to build a new wharf – that’s the place where the boats come in from the river to load and unload their cargo – John Haffey got the job. A few years after he did that job Annie Haffey was born, and *she* was your great-great-great grandmother. I’ll tell you more about her another time.

So Katherine and James came from Ireland, which is the country right next door to where you were born, but since then, for nearly 200 years, your family hasn’t been able to tear themselves away from the Ohio River. Your great uncles lived next to it, and your great grandparents, and now your aunts and uncles and cousins all have their houses a stone’s throw away from it. Your grandparents’ house overlooks it. And now, at this very moment, you’re at a camp just down the river from where your great-great-great-great-great grandparents lived. I think that’s very cool.

Love,

Mummy.

***

My little daughter thought that this was a rather unorthodox communication, a bit over the top, and she let me know it. Settling into the back seat of the car, her hair unwashed, her feet blackened from a week’s revelry in the woods, her teeth somewhat suspect after days of ‘brushing’ them with her finger, she inquired what on earth I’d been thinking.

‘Why did you write me such a long letter that it had to be stapled together?’ she asked.

‘Ah, was that a bit weird?’ I said.

‘Well, yes,’ she said. ‘And I don’t think she and I have *anything* in common.’

Well, I reckon that she’ll appreciate it all someday. Given the fascination she showed when visiting the grave of her great grandparents, that day might not be as far off as all that.

Publication Date Announced!

Photo credit Andrew Neel on Unsplash.

Photo credit Andrew Neel on Unsplash.

Once upon a time, I was a reader, a peruser of books in shops, an attender of literary festivals, a babe in the woods. I’m still the first three things, but as for the latter, because I’m an author now too, the scales have fallen from my eyes. In my former incarnation as a publishing innocent, I presumed that the new hardcover releases on the shelves, in their pristine, gorgeously designed dust jackets, had been completed by their writers only very recently. Not the previous week or the previous month, mind you – I wasn’t so naive as to think that the wheels of traditional publishing spin that quickly – but I reckoned that if the author turned in fairly ‘clean copy’, the time period between submission and publication would be short – mercifully short, from the vantage point of any author eager to see their work in print.

I don’t do drafts. Does that sound pompous? Before you judge, I’m not claiming to be some sort of Mozart. (Remember that famous scene in Milos Forman’s film Amadeus, where Salieri – having been assured by Mozart’s wife that her husband doesn’t make copies – is desperately rifling through reams of his rival’s scores, dumfounded, seeking and failing to find any evidence of corrections? It’s not quite like that.) What I mean to say is, I edit so stringently as I go along that my first version is always very close to the finished, accepted product. While some scribblers can pull off ‘free writing’, bashing out words and saving the painful business of editing for a later date, I’ve never been able to manage that. I wish I could, for the notion of being able to write freely is utterly intoxicating. Instead, I have to get the first sentence, the ‘way in’, absolutely right. That unlocks the next sentence, which must also be perfected until it, in turn, unlocks the path to the third sentence. If that sounds painfully obsessive-compulsive, you’re right. It is. But there’s a payoff at the end: the manuscript is virtually ready to go.

Ah, but as it turns out, that’s not how it works. Self-publishing is gloriously instant gratification, but in traditional publishing, no matter how ‘clean’ the copy, no matter how happy your editor might be, no matter how much the writer is chomping at the bit, there is much to do between submission and publication. The authors’ information from Little, Brown, my publishing house in the UK, says that one’s publicist and marketing team are assigned after submission, about nine months ahead of publication. That’s right. A human pregnancy and the “gearing up” period for a book’s publication take about the same amount of time – and if, like me, you’re a woman that’s given birth, you remember how long that felt.

All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age has been a fascinating book to write. On one hand, it’s directly focused on death, digital death, and digital afterlives. On the other, these topics are merely lenses, a pair of spectacles that I’ve donned to more closely examine identity, privacy, relationships and grief; our rapidly changing social mores; and the ethical, moral, and legal dilemmas posed by our modern digital existence. Death in the digital age is important to consider in itself, but it’s even more important because, looked at in depth, it really helps us think about how we’re living now. I’m an impatient sort of person anyway, but I’m particularly impatient now, because I can’t wait to share it with you.

All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age is out on 25 April 2019 from Robinson/Little, Brown UK.

“I know one of your secrets, Mummy”: What is privacy for?

Try this. For the next few days, as you move through the world – making your choices, reading the news, talking to your friends and family – set yourself the task of noticing how often the topic of privacy rears its head. Maybe it’s not called that; maybe it’s a kind of underlying theme, thrumming underneath the surface of a situation without being given its name. But it’s there. There are a dozen or more moments a day when we might be able to stop and say, “You know, this has a lot to do with privacy, really.” And just why is it such an ever-present theme? The answer won’t shock you.

Modern privacy is the hapless, weary lab rat of the information age, constantly scrutinised under the microscope, continually tested, always under investigation. We have to keep our eye on it, because it’s got a bit out of our control. We used to know what it was, you see: how it worked, how to govern it, what laws applied to it. But then – not gradually, not bit by bit, but quickly, in a tsunami of bytes – everything changed, and the concept of “privacy” mutated too. Every day privacy is tossed into the searingly hot crucible of the digital environment, its integrity challenged, its properties and limits shifting and morphing. This metaphor I’m using positions us as people who can study and control things, but that probably isn’t right for this context. That doesn’t represent our relationship with privacy at the minute, individually or collectively, in the online environment. We don’t feel in control of much of anything. We’re not clever scientists. We’re clueless smallholders closing our stable doors after all our horses have bolted, wondering how this happened, mouths agape, catching flies.

The Merriam-Webster definitions of “privacy” are sort of useless in the digital age, because they create as many questions as they answer. “Seclusion”? What’s that? When our virtual connectivity is taken into account, when are we ever apart from company or observation? What constitutes an “intrusion” these days, when we share so much of our personal data, knowingly or unknowingly? And “unauthorised”? If we wanted to be 100% clear about what we were and weren’t authorising, we’d be signing away the majority of our free time. Five years ago, The Atlantic reported that if we read and understood all of the privacy policies we encounter in a year, we’d lose 76 working days annually. Five years ago. I shouldn’t like to hazard a guess about much more time it would take in 2017.

The consequences of not reading the T&Cs of what you’re signing up to, with respect to privacy, came home to me recently. I listened to an episode of the Reply All podcast, all about whether Facebook is really “listening” to us via our smartphones. Following their instructions, and with a sense of foreboding, I did something I’d never done before – I looked into the advert settings to see how I’d been “categorised”.

My first reaction to this? Clarity. Ah-ha! That’s why I get all of these advertisements for products that would allow me to proclaim my connectedness or my allegiance to the United States; that might help me assert my “identity” as a dual national; or that would put me in touch with an advisor, someone who could save me from the fate of people like well-meaning Tom or Rebecca, who didn’t mean to fall afoul of the IRS while living in the UK but who then got the right tax advice and were never anxious again. (I hate those.) Fully half of my categories had to do with my “ex-pat” status, my distance from “home,” my separation from what Facebook divined to be key “family”. (The other half of my categories comprised a comprehensive list of all the Apple devices that I own.) My list of interests, on the other hand, portrayed me as a highly materialistic and vain sort of person, someone keen to purchase goods and service that would maintain and enhance my appearance. This also all made sense in terms of the adverts I typically get. (My abiding interest in tattoos came as a surprise to me, being completely free of skin art.)

My second reaction? Skin crawl. I knew that this wasn’t technically “unauthorised”. I simply hadn’t paid attention, hadn’t un/ticked certain boxes, hadn’t assiduously reviewed my settings at every app update. Even so – even though I knew such technologies existed in the world, and that we are all constantly, silently plugged into more algorithms than we can count – it felt creepy. I hadn’t realised my categories were visible to me; bringing them into the light and looking at them straight on had an “ick” factor that I didn’t anticipate.

Third reaction? Definite displeasure. Authorised or not, it did feel like an intrusion. But an intrusion on what? Into what? I didn’t really care, actually, that Facebook “knew” that I buy cosmetics, that I have a family, that I engage in travel, that I wear jewellery. Follow me or talk to me for five minutes, and you’ll figure this out. It’s hardly a secret source of shame; I don’t consider these data to be “private”. So what was my umbrage about? Why did it feel like such a liberty?

The questions I’ve found myself asking are not exactly about what privacy is. Instead, they’re about what privacy is for. I had that discussion with students yesterday on the MSc in Cyberpsychology at the University of Wolverhampton, when we were talking about whether dead people had the “right” to privacy. Traditionally, rights in general, and privacy in particular, are the province of “natural”, or living, persons. What good is “privacy” to a dead person? What’s it for? The answer, these days, is intimately connected to digital legacy. If an image of you is going to persist online after you’re dead, what do you want that image to be? Would you like to think you’ve got some say over that? When you think about someone altering or fundamentally messing with that image after you’re gone, or about someone logging in and reading your private messages, does that upset you? Would you like to believe that you’re the author, as much as possible, of your own lasting legacy?

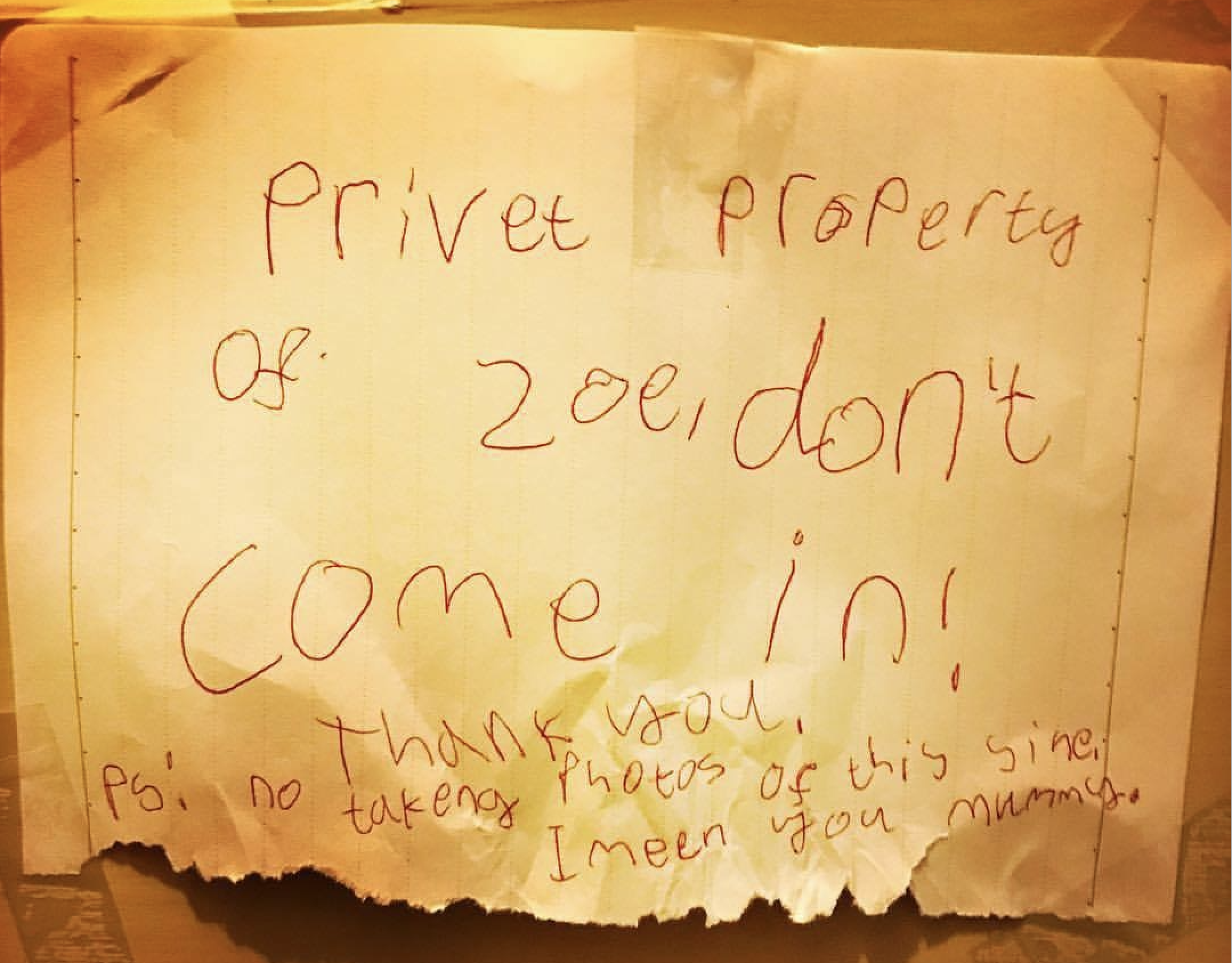

My daughter is seven years old. Over the summer, visiting the States (you know, the place from which I am expatriated), I took a lot of photos. Being the only one in the family with a camera constantly in hand, I serve as the chronicler. I posted dozens of images on Facebook and Instagram. They were there for the record, to be shared with the people who were there and who didn’t take snaps themselves, and to be enjoyed by friends back home in England. Zoe knows that I share these things and often encourages and expects it, but perhaps it had all got a bit much. One day I saw that the door of the room where she was staying was firmly closed, and Sellotaped onto it was a sign.

“Privet property of Zoe, don’t come in! Thank you. PS: No takeng photos of this sine. I meen you mummy.”

Naturally, I took a photo of it and posted it on social media.

I’m not a complete monster. This action was not unconsidered. I wasn’t free of doubt or compunction, but ultimately I went for it because I am mired in a particular belief. I believe that the record of her childhood that I have compiled, stored, and shared on Facebook captures her personality and development over the years in all of its beauty, hilarity, poignancy and wisdom. I think that it’s a Good Thing and that she’ll ultimately appreciate all of it. Of course I would say that, though. I am the biographer, the person who has taken virtually all of the decisions about what to disclose, what to select, what to share, and what to conceal about her life. I’m curating this show; I’m driving this train. Meeting adults in my circle of Facebook friends for the first time, my daughter is often astonished at the warm familiarity they show her, at their insider knowledge of her life. Her reputation has preceded her, a reputation for which her mother is largely responsible. “I don’t understand,” she said to me once. “Am I famous, or something?”

I laughed when she said that, but it was a guilty laugh. A while later, I had the opportunity to feel guilty again. She waited for her moment to confront me. I was driving.

“I know one of your secrets,” issued a severe-sounding voice from the back.

“One of my secrets?” I said, blankly. What could the child mean? “Do you think Mummy has a lot of secrets?”

There was a pause.

“You privately shared something that I said was private,” she said coldly. “I saw that photo of the sign on my door. It was on Melanie’s computer.”

“I’m sorry,” I replied weakly.

There was a pause again.

“It’s my choice,” she said, with emphasis.

That’s it. That’s the whole of it. There wasn’t anything secret behind that door. There wasn’t anything sensitive about that sign. But it was her sign, her writing, her room. It was her choice. Fundamentally, her privacy in that moment had nothing to do with that sign and everything to do with self-determination. She had attempted to limit the audience with which it was shared, I had overridden that attempt, and here I am doing it again.

These conversations with my daughter, and my little excursion into the midnight zone of my Facebook privacy settings, have helped clarify what I think the fundamental function of our privacy-focused behaviours are. Privacy is about self-determination. It’s about retaining the power to say this is who I am. This is what I value. This is how I choose to present myself to the world. This is how I identify, this is how I prioritise the different facets of myself. This is the access to me that I will allow you. Of all the things about myself that I consider to be important and valuable, “ex-pat” – a term I hate, a concept with which I no longer identify – is very last on the list. Facebook had it listed as the central feature of my existence.

So I asked Zoe if I could post this photo on this blog. She said yes. And then, methodically, I went through and removed every “ex-pat” category on my Facebook advert settings. I’ll choose how I classify myself, thanks very much.

I left the bits about fashion and travel alone.

(c) Copyright Elaine Kasket 2017

Would you like to share your story?

We’re reaching a point where most of us have personal experience of some kind of intersection between death and the digital world. People may hear about the loss of friends and family via social media. They may struggle with online platforms for control over or access to information about their loved ones’ digital legacies. They may use a friend’s Facebook site for mourning and memorialising them after they are gone. They may wonder what will happen to their own online material after they die, and some may even decide they’d like to maintain their social lives from the Great Beyond. Throughout the remainder of 2017 and the start of 2018, I’m writing a book for popular audiences about all of these phenomena. It’s called All the Ghosts in the Machine, and it’s published by Little, Brown UK and an as-yet-to-be-determined publishing house in the US.

If you have a story that you’d like to share with me, I would love to speak to you about a possible interview for inclusion in this book. Please do reply to this post or email me on info@alltheghostsinthemachine.com . I also speak frequently about this topic to various audiences, including the public, psychological practitioners, and academics, so if you are a journalist, producer, or representative of an organisation that would like to discuss this with me, please feel free to get in touch as well.

For more about the book, read on! This is an extract from the original proposal, describing what All the Ghosts in the Machine is about.

This is a book about unintended consequences. Mark Zuckerberg and his colleagues launched Facebook to connect students at Harvard, not to create a mixed-use social networking platform and digital cemetery. Skype was designed to enable us to chat to one another, not to live stream funerals. In short, when the whiz kids of Silicon Valley created the technologies that we now use to capture, store and share massive amounts of data, it was the living consumer that they had in mind. And yet here we are, the dead and the living, still segregated in the corporeal world, but mixing and mingling like mad in the digital sphere. That situation is tantalizing and comforting to some, surreal and horrifying to others. Whatever one’s gut reaction, though, those who think that this phenomenon does not directly affect them will be surprised at the number of ways that this assumption is untrue. We are at a tipping point of awareness: more of us are realising that one day this issue will prove personally meaningful to us, but most of us have no idea just how complicated and multifaceted this issue is.

In the realm of death, as in much else, the digital revolution changes everything. It has been said that we are not truly dead while our names are still spoken. In a technological landscape where it is more difficult to forget than to remember, the dead are still spoken about a lot – in fact, they may continue to “speak” themselves. The ability to stick around in digital form holds out the prospect of a kind of immortality. Through making connections with our dead easier than ever before, these very modern technologies may draw us back to quite ancient ancestor-veneration practices; our predecessors’ presence is more apparent and actively influential in society than has ever been the case before. Realizing that it is not just the great and famous who may have their legacies preserved, but all of us, do we make different choices in our lives? How do we respond to the persistent echoes and reflections of deceased loved ones online, or otherwise in digital form? Knowing that one day we will be one of them, how do we manage our own data? What happens when corporations compete with us for control of those data? And could the phenomenon of technological obsolescence eventually prove that a granite headstone memorial was the better option all along?

This book is about all levels of this fascinating and thorny territory: psychological, sociological, practical, legal, spiritual, ethical, and commercial. It will tell the stories of people who have confronted unexpected and complex dilemmas at the many junctions where death and life meet online, help readers with their own confrontations with these challenges, and explore the implications that these fascinating new developments hold for all of us.

The Death Goes Digital podcast!

A lot has happened since I last posted on my WordPress site! I got a fabulous agent – Caroline Hardman of Hardman & Swainson – and secured a book deal with Little Brown UK. I’m extremely excited about writing All the Ghosts in the Machine, which is my first non-academic book. I spend most of my days writing at this desk.

A few weeks back I sat at that same desk and had a great conversation about the book and the topics covered in it with Pete Billingham of Death Goes Digital. That conversation was lovingly crafted into a podcast, which has just been published today. Please do have a listen – you can also download it as a podcast from Apple – and if you have a story of death in the digital age that you think needs to be told, email me on info@alltheghostsinthemachine.com!