When I arrived at St. Leonard’s on Shoreditch High Street, the film crew looked distinctly gloomy. Their solemnity wasn’t due to their being about to descend into the dusty crypts under this 1740 building, at least not yet; at that point, it was because some organisation or another was holding a big party in the churchyard. The sound system was just kicking into gear, pumping out music on a sunny Sunday and threatening to interfere with the audio for the mini-documentary we were there to film. A party atmosphere wasn’t what the director had been anticipating or intending, and furthermore, we were having trouble gaining access to the underworld beneath the church. The caretaker hadn’t yet arrived to unlock the door, which, when we arrived, was blocked with rubbish and festooned with a string of bright yellow happy-face balloons. When he eventually appeared, though, we realised that there was no cause for concern, as far as filming was concerned. Down in the depths, behind and beneath thick walls and floors, you could barely tell whether it was day or night outside, much less hear evidence of revelry and dancing. We wended our way through dim corridors, using our phones as torches and looking for places to film.

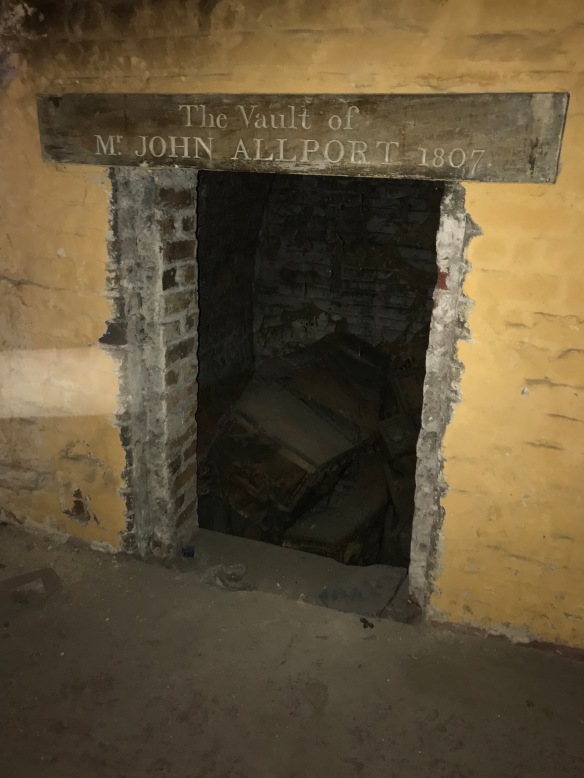

On one hand, this was an incongruous place to be shooting a film on ‘E-Life After Death’. Modern people’s online ‘afterlives’ or digital traces are made up of odourless bits of code and complex arrangements of colourful pixels, but our environment in the crypt was an entirely different sensory experience. While the atmosphere outside was sunny and warm, down there it was cool, grey, and slightly damp. Every surface we touched, accidentally or on purpose, left thick smears of dust on our skin and clothes. No one said it out loud, but I was conscious that – along with the musty smell – I was likely inhaling minute particles of humans that had been dead for hundreds of years. Doors to vaults were virtually all open or absent, with the bricks that had once walled them off scattered about the uneven floor, tripping us up as we arranged cameras, lights, and filming positions. Through the gaping entrances we saw coffins stacked atop one another, some broken or turned on their ends. ‘Oh god, that’s a jaw bone, isn’t it?’ said one crew member, pointing the light from his phone into a collapsing casket. ‘Shit,’ said another, treading on something. ‘I’ve stepped on a bone. Oh, it’s a stick. No, shit, it’s a bone, look, it’s a human bone.’ Working out whether he’d directly disturbed already-scattered human remains seemed to really matter to him, almost as though he needed to determine whether he’d done something ‘wrong,’ whether he should feel unnerved or even guilty.

I was more nonplussed than they, having visited quite a few crypts in my time. This is partly thanks to the periodic ‘open days’ held in the Magnificent Seven cemeteries in London, which usually involve opening the crypts too. Still, I could understand their unease. Disturbing physical human remains isn’t usually something we undertake deliberately or view lightly. But interestingly – and at the heart of the documentary we were making – is the fact that we encounter the digital remains of the dead online all the time. They are everywhere we go, whether they announce themselves or not. They’re on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Trip Advisor, Amazon, LinkedIn. They’re on the comment threads under news stories, on the blogs, on websites of every stripe. And if you think about it, we often disturb those remains.

Strangers like us had clearly been down in these crypts many times before, and the resting place of nearly every 18th- and 19th-century person buried there had been disturbed, disrespected, and cluttered up with rubbish. Maybe you would never do that, but online you might find yourself picking over the digital remains of a dead person like a jackal. It’s not just strangers that do it. Sure, trolls can come along with their cruel insults and senseless smears, but well-meaning parties disturb digital remains too. Family may deny access to or even destroy digital legacies, so that other mourners who arrive at the online graveside find a barred door, or an empty vault. Corporations, too, have their rules about what can and cannot be done with digital remains, with the result that the memories of the deceased that are preserved don’t always constitute the peaceful, respectful picture that some might wish. When a company that stores or manages a deceased person’s data goes out of business, they may cart digital remains away with them, robbing the grave as they file for bankruptcy. So think about it. We’re perpetually accessing, embroidering upon, editing, destroying or otherwise messing with digital remains online, and yet it doesn’t give us anywhere near the same pause that knocking in a crypt door would (hopefully) provoke. Maybe it seems obvious why that is. But maybe it’s also worth reflecting on why we see it so differently.

Look out for the eventual documentary on BBC Ideas, airing date to be determined.